|

But in early spring of 2000, while living on New York's Upper West Side, something unusual happened. Faced with two winter-deflated tires on my Raleigh M-20, I walked the bicycle to a shop on Columbus and 81st in search of air. But when I arrived, the store was closed, its final customer being escorted to the door. He was a stocky, muscular man with grayish hair, and as he exited I knew almost immediately—even under his bike helmet and sunglasses—that it was Robin Williams. And he knew that I knew.

"Hi, how you doing?" he said casually.

"Hi," I said back, just as casually. (As a longtime New Yorker, I was obliged to treat any celebrity encounter like an exchange with the mailman.)

I stepped aside to let him wheel his Very Expensive Bike past me, then moved quickly to address the proprietor locking the door behind him. Through the glass I pleaded my case for five minutes with the shop's air hose, which had already been pulled inside. But the man, a longtime New Yorker himself, was obliged to brusquely tell me to come back tomorrow. Before I could come up with any good curses, I heard a gentle voice behind me.

"I have a pump you can use."

|

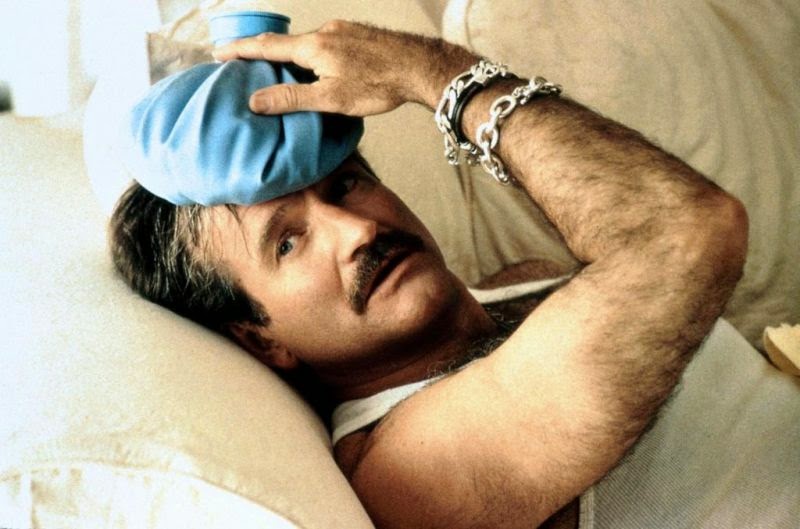

| Photo: Bill Reitzel |

"Are you sure?" I asked, uncertain how much I was supposed to resist a celebrity's offer of assistance.

But he was already unclipping a small, metallic cylinder from the bike's frame. "I'm not really sure how it works," he said, "but if you can figure it out you're welcome to use it."

"Thanks," I replied. I took the tiny hand pump from him (in my memory, it glinted in the fading sunlight), and was immediately baffled by the strange celebrity technology.

"Why don't I try?" he said.

And then Robin Williams—Oscar winner, star of two of my favorite NYC movies (Moscow on the Hudson and The Fisher King), and one of the sharpest, funniest minds in the business—was bending over my $225 cruiser, attaching the pump to my front tire, and pumping away.

"This thing works much better on your tires than mine," he said.

I glanced at his own tires, so thin they barely poked into three-dimensional space. Each one probably cost more than my entire bike.

"Is that enough?" he asked, growing winded.

I squeezed the still soft front tire.

"Just a little more," I said. I wondered how little air I could get away with and still ride. Robin continued pumping as pedestrians surged around us. "A little more," I said, feeling guilty but also strangely powerful.

"Okay, that should do it," I said finally. "Great! Now the back one."

|

| The Birdcage |

"I love your work," said one.

"Thank you," the actor replied, smiling graciously.

"Nanu-nanu," said another.

|

| Mork and Mindy |

"More," I said timidly. "A little more..."

Finally, we were done. The tires weren't at full pressure, but they were full enough for me to ride around until tomorrow. Robin looked like he could use some air himself. I thanked him profusely, we shook hands, and I said I wished there was something I could do in return. He said not to worry about it, wished me a great day, then got on his Tron-like cycle and we pedaled off in opposite directions.

I wobbled past a parking sign, scraping the curb, as I tried to process everything that had just happened. Robin Williams had pumped my tires. Both of them. On the street. In front of everyone. Patch Adams or no, he had definitely regained my respect. No matter how schmaltzy his recent movies, I now realized they came from a real place: the man truly was a mensch, a genuinely good human being. And no doubt there would be plenty of good films to come.

|

| Popeye |

For an appreciation of the subtlety he could bring to comedy, see his hilariously contained work with Nathan Lane in Mike Nichol's The Birdcage (1996), where in addition to playing a convincing gay man he holds his own as—of all things—the movie's straight man. Along with family comedies Popeye and Hook is the enjoyable Jumanji (1995), while World's Greatest Dad (2009), despite its comforting-sounding title, is as unsuitable for family viewing as you can get. A low-key, late-career acting triumph, this comedy of discomfort was written and directed by none other than Bobcat Goldthwaite, and touches unnervingly close to Williams' own situation at the time of his death.

One final streaming recommendation is less obvious but perhaps most fitting: the first half of "Barney/Never," a third-season episode of Louis C.K.'s peerless FX series, Louie. "Barney" is a short, slow-burn tale of two despairing and lonely men sharing laughs and quiet company in the contemplation of another's death. It makes for a funny, odd and poignant send-off for a man who brought such a variety of pleasures to the world.

Rest in peace, Robin. Thanks for your brilliance, your humor, and your generosity. And thanks for the air when a fellow New Yorker needed it.

http://www.theguardian.com/film/from-the-archive-blog/2014/aug/12/robin-williams-films-reviews-archive-died http://www.theguardian.com/film/2010/sep/20/robin-williams-worlds-greatest-dad-alcohol-drugs

No comments:

Post a Comment